two dose fractionation modes using carbon ion beam therapy in the lymphnode drainage area for lung

Clinical report of two dose fractionation modes using carbon ion beam therapy in the lymphnode drainage area for lung cancer

中华放射肿瘤学杂志 2023 年3 月第 32 卷第 3 期 Chin J Radiat Oncol, March 2023, Vol. 32, No. 3

Pan Xin1, Zhang Yihe1, Li Xiaojun1, Ma Tong1, Wang Xin1, Yang Yuling1, Chai Hongyu1, Qin Tianyan2, Lyu Caixia2, Li Pengqing2, Ye Yancheng1, Zhang Yanshan1

1Department of Radiation Oncology, Heavy Ion Center, Wuwei Cancer Hospital of Gansu Province, Wuwei 733000, China; 2Registration / Follow ‐ up Center, Heavy Ion Center, Wuwei Cancer Hospital of Gansu Province, Wuwei 733000, China

Corresponding author: Zhang Yanshan, Email: 13830510999@163.com

【Abstract】 Objective To compare the adverse reactions, efficacy and survival rate of carbon ion beam irradiation in the elective lymph node (ENI) drainage area of locally advanced non‑small cell lung cancer (LA‑NSCLC) with relative biological effect (RBE) dose of 48 Gy using 16 and 12 fractions. Methods A total of 72 patients with pathologically confirmed LA ‑ NSCLC admitted to Wuwei Heavy Ion Center of Gansu Wuwei Tumor Hospital from June 2020 to December 2021 were enrolled and simple randomly divided into groups A and B, with 36 patients in each group. Patients in groups A and B were treated with carbon ion beam irradiation to the lymph node drainage area with 48 Gy (RBE) using 16 and 12 fractions. The acute and chronic adverse reactions, efficacy and survival rate were observed. The survival curve was drawn by Kaplan‑Meier method. Difference test was conducted by log‑rank test. Results The median follow‑up time was 13.9 (8.8‑15.7) months in group A and 14.6 (6.3‑15.9) months in group B. Sixteen (44.4%) patients were effectively treated in group A and 9 (25%) patients in group B. Thirty ‑ four (94.4%) cases achieved disease control in group A and 30 (83.3%) cases in group B. Statistical analysis showed that the overall survival rate in group B was similar to that in group A (χ2=1.192, P=0.275). Comparison of planning parameters between two groups showed CTV volume, Dmean, V5 Gy(RBE), V20 Gy(RBE) and V30 Gy(RBE) of the affected lung, cardiac V20 Gy(RBE), V30 Gy(RBE) and Dmean, esophageal V30 Gy(RBE), V50 Gy(RBE), Dmax and Dmean, Dmax of the trachea and spinal cord had no significant difference (all P>0.05). No grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions occurred in the enrolled patients during treatment and follow‑up. No statistical differences were observed in the acute radiation skin reaction (χ2=5.134, P=0.077), radiation esophagitis (χ2=1.984, P=0.371), and advanced radiation pneumonia (χ2=6.185, P=0.103) between two groups. Conclusions The two dose fractionation modes of carbon ion therapy system are equally safe in the mediastinal lymphatic drainage area of LA‑NSCLC, and the adverse reactions are controllable. The long‑term efficacy still needs further observation.

【Key words】 Radiotherapy, carbon ion; Carcinoma, non‑small cell lung; Elective lymph node drainage area radiotherapy; Adverse reactions; Short‑term efficacy

Fund programs: Key Science and Technology R&D Plan of Gansu Province ‑ Construction of Heavy Ion Treatment Center for Social Development (19YF3FH001); Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province ‑ 2021 Innovation Base and Talents Program of Science and Technology Department of Gansu Province (21JR7RH896)

Currently, the incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer remain high worldwide. One of the main reasons for the poor prognosis of lung cancer patients is that the disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, making surgical intervention no longer feasible. For stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, surgical treatment can achieve a 10-year survival rate of up to 92% [1]. Therefore, early detection of lung cancer, accurate staging, and selection of appropriate treatment strategies are of great significance for improving patient prognosis.

Verhagen et al. [2] reported that even after radical surgery, the postoperative recurrence rate for stage I NSCLC patients remains at 25%–50%, with lymph node metastasis being one of the primary factors contributing to recurrence. In the context of surgical treatment for lung cancer, lobectomy combined with lymph node dissection is the standard recommended approach. For example, both the 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the 2020 Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) guidelines recommend hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection even for T1-stage lung cancer. Before the use of CT for radiotherapy planning, elective nodal irradiation (ENI) was the standard treatment modality for NSCLC radiotherapy, with the advantage of reducing regional lymph node failure rates [3]. However, because ENI includes the primary tumor, metastatic lymph nodes, and clinically negative lymph node drainage areas in the irradiation field, excessive exposure of normal tissues such as the lungs, esophagus, and heart often leads to severe complications like radiation pneumonitis and esophagitis. This, in turn, makes it difficult to effectively escalate the radiation dose to the primary tumor. The unique physical and biological advantages of carbon ion beams make ENI a viable option.

This study employed a carbon ion therapy system to treat locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC). The lymph node drainage area was irradiated with carbon ion beams at a relative biological effectiveness (RBE) dose of 48 Gy (RBE), divided into either 16 or 12 fractions. The study aimed to observe acute and chronic adverse reactions, efficacy, and survival rates, thereby providing a reference for the formulation and optimization of carbon ion radiotherapy plans for LA-NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient Data: From June 2020 to December 2021, 72 pathologically confirmed LA-NSCLC patients treated at the Heavy Ion Center of Wuwei Cancer Hospital in Gansu Province were enrolled. All patients underwent cranial MRI, chest CT, and PET-CT scans and were staged according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system. Patients with T1-3N1-2M0 and T3-4N0-1M0 stages were randomly divided into Group A and Group B, with 36 patients in each group. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuwei Cancer Hospital (Approval No. 2021-Ethics Review-05).

2. Carbon Ion Therapy

(1) Treatment Position: Patients were placed in the supine position on the treatment couch with a fixed pillow under the head. Both arms were raised and crossed above the head with elbows fully extended. A thermoplastic chest mask and vacuum cushion were used for immobilization. CT scans included both non-contrast and contrast-enhanced sequences, along with 4DCT scans. The slice thickness and interval were both set at 3 mm, and the scanning range extended from the cricothyroid membrane to the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra.

(2) Target Delineation: Target volumes were contoured using standardized protocols (with MR or PET-CT fusion when necessary).

• GTV: Gross tumor volume visible on imaging (referenced to contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, or PET-CT).

• GTVnd: Mediastinal metastatic lymph nodes, defined as those with a short-axis diameter ≥1 cm and/or PET-CT positivity and/or pathological confirmation via endoscopic ultrasound.

• CTV: GTV + GTVnd with a 0.5 cm margin + elective nodal irradiation (covering the involved field of metastatic lymph nodes and prophylactic areas based on nodal metastasis risk, typically including nodal stations II, IV, V, and VII).

• ITV: Internal target volume accounting for CTV motion observed on 4DCT.

• PTV: ITV expanded by 3–5 mm, with adjustments made near organs at risk.

Treatment planning was performed using the Ci-Plan Carbon Ion Treatment Planning System (version 1.0). Prescription doses:

• Group A: 48 Gy (RBE) in 16 fractions to the lymph node drainage area.

• Group B: 48 Gy (RBE) in 12 fractions to the lymph node drainage area.

Both groups received a total dose of 72 Gy (RBE) to the primary tumor.

3. Follow-up: Patients were followed up through outpatient visits for at least six months, starting from the first day after radiotherapy completion. The first two follow-ups were conducted monthly, followed by quarterly visits until February 28, 2022.

4. Efficacy and Adverse Event Evaluation: Clinical observations were performed on enrolled patients. Acute adverse events were assessed using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0, while late adverse events were evaluated according to Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria. Treatment efficacy was determined based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1). Local control rate = (complete response + partial response + stable disease)/evaluable cases × 100%; Time to progression (TTP) was defined as the duration from radiotherapy initiation to local recurrence, and overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from radiotherapy initiation to death from any cause or the last follow-up.

5. Statistical Analysis: Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s), while categorical variables were presented as percentages. The t-test and chi-square test were used for count data analysis. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and short-term adverse events were compared using the chi-square test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

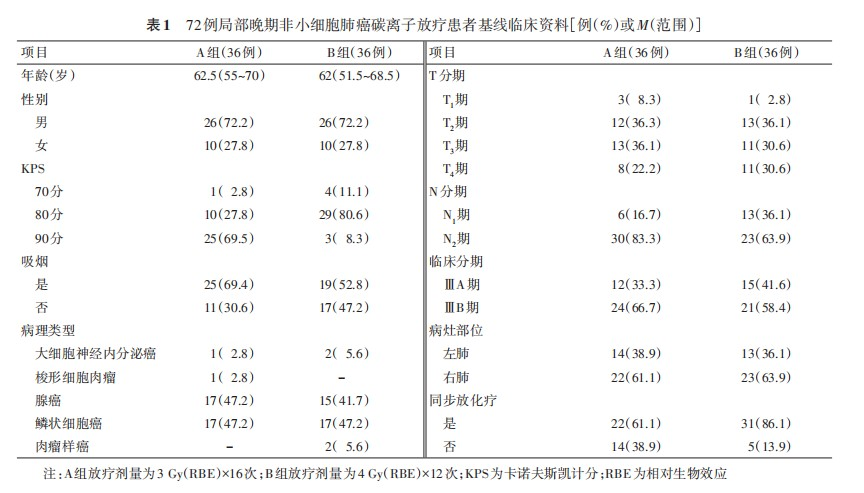

1. Baseline Characteristics: The study included 72 pathologically confirmed NSCLC patients. Both Group A and Group B had a male-to-female ratio of 26:10 (72.2%:27.8%). The median ages were 62.5 years (range: 55–70) in Group A and 62 years (range: 51.5–68.5) in Group B. In terms of pathological types, squamous cell carcinoma (17 cases, 47.2%) and adenocarcinoma (17 cases, 47.2%) accounted for the majority in Group A, while Group B had 17 cases (47.2%) of squamous cell carcinoma and 15 cases (41.7%) of adenocarcinoma. According to the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) guidelines and individual patient conditions, 22 patients (61.1%) in Group A and 31 patients (86.1%) in Group B received concurrent chemotherapy. Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics showed a statistically significant difference in Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scores between the two groups (χ²=28.39, P<0.001), while no significant differences were observed in other parameters. Detailed patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

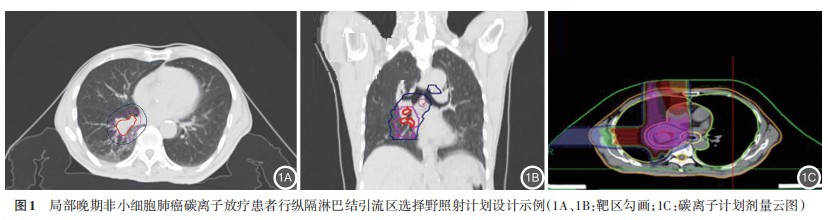

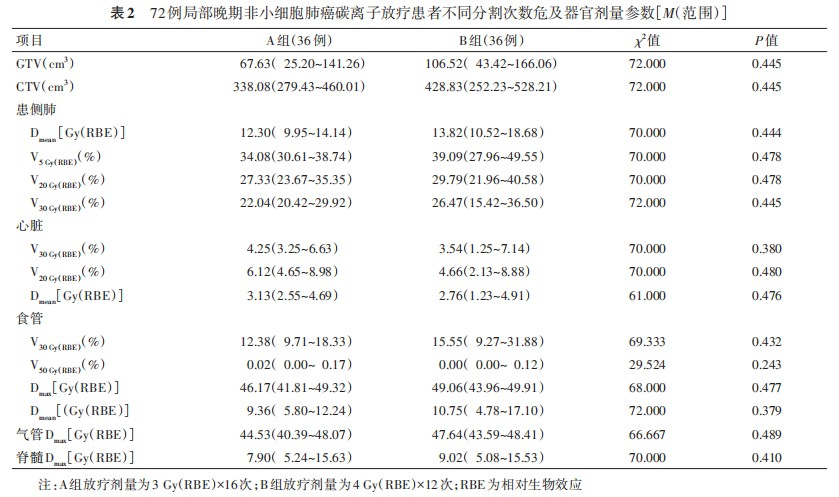

2. Treatment Outcomes: According to the study design, both groups received 48 Gy (RBE) to the lymph node drainage area, but with different fractionation schemes: 3 Gy (RBE) × 16 fractions in Group A and 4 Gy (RBE) × 12 fractions in Group B. The treatment plan design is shown in Figure 1. To evaluate dose distribution to organs at risk (OARs), we conducted statistical analysis of relevant dosimetric parameters. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the following parameters: GTV volume, CTV volume, mean lung dose (Dmean), V5 Gy(RBE), V20 Gy(RBE), and V30 Gy(RBE) of the ipsilateral lung; V20 Gy(RBE), V30 Gy(RBE), and Dmean of the heart; V30 Gy(RBE), V50 Gy(RBE), maximum dose (Dmax), and Dmean of the esophagus; Dmax of the trachea; and Dmax of the spinal cord (all P>0.05). Detailed data are presented in Table 2.

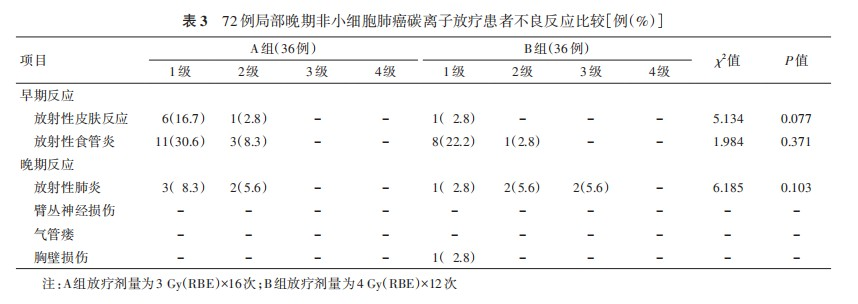

Patients in both Group A and Group B completed the prescribed carbon ion therapy as planned. No grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions were observed in any patient during treatment or follow-up. Based on the comparison of dosimetric parameters, no significant differences were found in the parameters of organs at risk between the two groups. However, due to differences in disease conditions, some patients received chemotherapy during carbon ion therapy.

We further analyzed the early and late adverse reactions in the two groups. The results showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the occurrence of grade 1-2 acute radiation dermatitis (χ²=5.134, P=0.077), radiation esophagitis (χ²=1.984, P=0.371), and late radiation pneumonitis (χ²=6.185, P=0.103). Detailed data are shown in Table 3.

3. Patient Prognosis

(1) Comparison of Short-term Efficacy Between the Two Groups: The follow-up period for all patients in this study ended on February 28, 2022. All enrolled patients were effectively followed up, and valid follow-up data were obtained. The median follow-up time was 13.9 (8.8–15.7) months in Group A and 14.6 (6.3–15.9) months in Group B. During the follow-up period, 1 case (2.8%) of in-field recurrence was observed in Group A, and 2 cases (5.6%) of in-field recurrence were observed in Group B. The remaining cases of disease progression involved distant metastases or new metastatic lesions. Among them, 16 cases (44.4%) in Group A achieved effective treatment, compared to 9 cases (25.0%) in Group B, with no statistically significant difference (χ²=3.003, P=0.083). In terms of disease control, 34 cases (94.4%) in Group A and 30 cases (83.3%) in Group B achieved disease control, with no statistically significant difference (χ²=2.250, P=0.134).

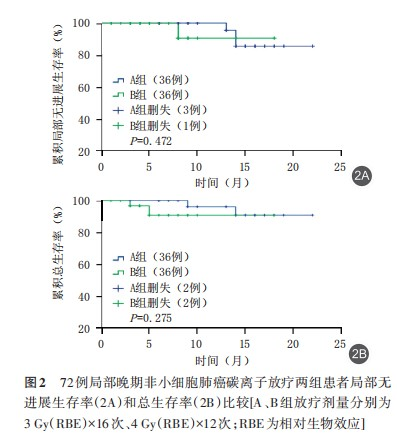

(2) Comparison of Survival Status Between the Two Groups: In this study, survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method to analyze the local control rate and overall survival of patients in both groups during the follow-up period, and their survival status was compared. The log-rank test was used for difference analysis. The results showed that the local control rate (χ²=0.517, P=0.472) and overall survival rate (χ²=1.192, P=0.275) were similar between Group B and Group A. The median local recurrence-free survival (LRFS) times were 20.8 months (95% CI: 19.63–20.06) in Group A and 17.1 months (95% CI: 15.39–18.79) in Group B. The median overall survival (OS) times were 21.1 months (95% CI: 20.01–22.29) in Group A and 16.8 months (95% CI: 15.27–18.42) in Group B. No statistically significant differences were observed (P>0.05), indicating that the overall survival of the two groups was similar at the end of the follow-up period. See Figure 2.

Discussion

Regional lymph node metastasis is a major factor affecting the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). During lobectomy, it is recommended to simultaneously remove intrapulmonary lymph nodes and mediastinal lymph nodes. However, despite the use of expected radical treatments, 25%–50% of early-stage lung cancer patients still experience recurrence during follow-up, suggesting that isolated tumor cell dissemination through the lymphatic system and micrometastases have already occurred early in the disease, which negatively impacts patient prognosis [4].

The extent of elective nodal irradiation (ENI) includes the primary tumor, metastatic lymph nodes, and clinically negative lymph node drainage areas, resulting in the inclusion of excessive normal tissues such as the lungs, esophagus, and heart within the radiation field. This increases the likelihood of severe complications such as radiation pneumonitis and esophagitis, making it difficult to significantly increase the radiation dose. Studies have shown that the recurrence rate in the lymph node drainage area after radiotherapy for NSCLC patients is 8%, while the recurrence rate within the primary tumor area is as high as 65% [5]. Therefore, in cases where the control of the primary lesion is unsatisfactory, the treatment target area does not need to include prophylactic ENI, and involved-field irradiation (IFI) alone may be sufficient. Traditional radiotherapy for locally advanced NSCLC (LA-NSCLC) has included lymph node drainage areas, i.e., ENI, as demonstrated in the RTOG 73-01 clinical trial [6]. However, many studies have shown that ENI does not provide additional benefits in terms of local control or survival rates [7]. Given the high recurrence rate in the lymph node drainage area (8%) compared to the primary tumor area (65%) with traditional irradiation methods, the treatment target area does not need to include prophylactic ENI, i.e., IFI, when the control of the primary lesion is unsatisfactory. Omitting ENI can significantly reduce the planning target volume (PTV), allowing for an increase in the radiation dose to the primary tumor and metastatic lymph nodes without increasing treatment-related complications.

A meta-analysis by Li et al. [8] in 2016 concluded that there is no difference in regional lymph node recurrence between IFI and ENI for LA-NSCLC, and the evidence is stable and reliable. Multiple studies have shown that LA-NSCLC is highly resistant to conventional fractionated radiotherapy, with local-regional failure rates exceeding 60% after concurrent chemoradiotherapy [9]. From a radiobiological perspective, there are compelling reasons to use heavy ion therapy to improve local control in these patients. When charged heavy ions interact with matter, they produce the highest linear energy transfer (LET) among currently available clinical radiation modalities [10]. This results in unique double-strand DNA damage, a lower oxygen enhancement ratio, and a higher relative biological effectiveness (RBE), which is three times greater than that of photon radiotherapy [10]. As a result, patients can achieve a primary tumor dose of over 72 Gy (RBE) and a drainage area dose of 48–52 Gy (RBE) with fewer adverse reactions, potentially ushering in a new era of clinical radiotherapy for lung cancer.

Saitoh et al. [11] analyzed six NSCLC patients treated with carbon ion therapy between 2013 and 2014. The patients received a tumor dose of 64 Gy (RBE) in 16 fractions and a prophylactic dose of 40 Gy (RBE) in 10 fractions to the regional lymph node drainage area. The median follow-up period was 26 months, with 1-year and 2-year overall survival (OS) rates of 83% and 50%, respectively, and progression-free survival rates of 33% at both time points. One case of grade 2 esophagitis and one case of grade 2 pneumonia were observed, with no adverse events greater than grade 3. The National Institute of Radiological Science (NIRS) in Japan treated 36 lung cancer patients with lymph node metastases between 2000 and 2010, delivering 48 Gy (RBE) in 12 fractions. The 3-year OS and local control rates were 52.9% and 100%, respectively, with no grade 2 or higher early or late adverse events. The median dose for prophylactic irradiation of the regional lymph node drainage area at NIRS was 49.5 Gy (RBE) [12-13].

Based on the above evidence and rationale, this study adopted ENI to irradiate the mediastinal lymph node drainage area in LA-NSCLC patients treated with carbon ion therapy, with a prescription dose of 48 Gy (RBE), and an additional 24 Gy (RBE) boost to the primary tumor lesion, resulting in a local dose of 72 Gy (RBE) to the primary tumor.

Heavy ion therapy often employs a hypofractionated regimen, reducing the total treatment time while achieving higher biological effects [14]. Analysis has shown a moderate linear relationship between tumor biological effective dose and overall survival, with each 1 Gy increase in biological effective dose improving the OS rate by 0.36%–0.7% [15]. Therefore, we designed two regimens in this study: 48 Gy (RBE) in 16 fractions and 48 Gy (RBE) in 12 fractions, to observe treatment efficacy and adverse reactions. In this study, the median follow-up times for Groups A and B were 13.9 (8.8–15.7) and 14.6 (6.3–15.9) months, respectively. The treatment efficacy rates were 44.4% and 25.0%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (χ²=3.003, P=0.083). The disease control rates were 94.4% and 83.3%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (χ²=2.250, P=0.134). However, local recurrence occurred in both groups during the follow-up period. Based on current evidence, concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced lung cancer typically delivers 60 Gy to the primary tumor and positive lymph nodes. In this study, both groups received 48 Gy (RBE) of carbon ion irradiation to the ENI. This raises the question of whether the local dose to positive lymph nodes is insufficient. Would further boosting the dose to positive lymph nodes improve local control rates? These are questions we are considering. Currently, all patients are under follow-up, and we plan to design related studies in the next phase to address these questions.

In addition, we analyzed the overall prognosis of the two groups. Using the Kaplan-Meier method to plot survival curves, the results showed that the overall survival rates of Group B and Group A were similar (χ²=1.192, P=0.275). This may be due to the higher single-fraction dose, but the total dose to the local tumor was not increased. Additionally, the follow-up time may not have been long enough. We will report long-term clinical observation data in subsequent studies.

A retrospective study by NIRS between 1995 and 2015 analyzed the clinical data of 141 patients with LA-NSCLC treated with carbon ion therapy. The results showed that the recommended tumor dose was 72 Gy (RBE) in 16 fractions, and for patients with regional lymph node metastases, the lymph node drainage area was irradiated with 49.5 Gy (RBE) in 16 fractions. One patient (0.7%) experienced a grade 4 (mediastinal hemorrhage) acute adverse event, five patients (3.5%) experienced grade 3 radiation pneumonitis, and one patient (0.7%) experienced a grade 3 bronchial fistula [16]. In this study, no grade 3 or 4 severe adverse events occurred in either group during treatment or follow-up. The main adverse events were grade 1 or 2 acute skin reactions and/or esophageal reactions, and most patients did not require medication or only needed local mucosal protectants to alleviate symptoms. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of adverse events or treatment plan parameters related to organ at risk, demonstrating the safety and good tolerability of both fractionation regimens.

In conclusion, the two fractionation regimens of the carbon ion therapy system demonstrated safety and good tolerability in the elective irradiation of the mediastinal lymph node drainage area for LA-NSCLC. The short-term efficacy comparison showed no significant difference between the two regimens, which may be related to the short follow-up time. Long-term follow-up data will be reported in subsequent studies. However, based on the current data, using fewer fractions can shorten the total treatment time, thereby improving the clinical utilization rate of the carbon ion therapy system and conserving medical resources. From this perspective, it may provide valuable reference information for treatment planners.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Pan Xin, Zhang Yanshan: Designed the study protocol, implemented the research, and wrote the manuscript. Zhang Yihui, Li Xiaojun, Ye Yancheng: Collected clinical data, proposed research ideas, provided technical guidance, and revised the manuscript. Qin Tianyan, Ma Tong: Conducted literature reviews and data analysis. Other contributors: Participated in the research.

References

[1] Takahashi W, Nakajima M, Yamamoto N, et al. A prospective nonrandomized phase I/II study of carbon ion radiotherapy in a favorable subset of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [J]. Cancer, 2015,121(8):1321-1327. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.29195.

[2] Verhagen AF, Bulten J, Shirango H, et al. The clinical value of lymphatic micrometastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2010,5(8):1201-1205. DOI: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e29ace.

[3] Sulman EP, Komaki R, Klopp AH, et al. Exclusion of elective nodal irradiation is associated with minimalelective nodal failure in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2009,4:5. DOI: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-5.

[4] Lee CB, Stinchcombe TE, Rosenman JG, et al. Therapeutic advances in local-regional therapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: evolving role of dose-escalated conformal (3-dimensional) radiation therapy[J]. Clin Lung Cancer, 2006, 8(3): 195-202. DOI:10.3816/CLC.2006.n.047.

[5] Perez CA, Stanley K, Rubin P, et al. A prospective randomized study of various irradiation doses and fractionation schedules in the treatment of inoperable non-oat-cell carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group[J]. Cancer, 1980,45(11):2744-2753. DOI: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800601)45:11<2744::aid-cncr2820451108>3.0.co;2-u.

[6] Emami B, Mirkovic N, Scott C, et al. The impact of regional nodal radiotherapy (dose/volume) on regional progression and survival in unresectable non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG data[J]. Lung Cancer,2003, 41(2): 207-214. DOI: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00228-9.

[7] Machtay M, Paulus R, Moughan J, et al. Defining local-regional control and its importance in locally advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2012, 7(4): 716-722. DOI: 10.1097/JTO. 0b013e3182429682.

[8] Li RJ, Yu L, Lin SX, et al. Involved field radiotherapy (IFRT) versus elective nodal irradiation (ENI) for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of incidence of elective nodal failure (ENF) [J]. Radiat Oncol,2016,11(1):124. DOI: 10.1186/s13014-016-0698-3.

[9] Wang SL, Liao ZX, Wei X, et al. Analysis of clinical and dosimetric factors associated with treatment-related pneumonitis (TRP) in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with concurrent chemotherapy and three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT)[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2006, 66(5): 1399-1407. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.1337.

[10] Durante M, Loeffler JS. Charged particles in radiation oncology[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2010, 7(1): 37-43. DOI:10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.183.

[11] Saitoh JI, Shirai K, Abe T, et al. A phase I study of hypofractionated carbon-ion radiotherapy for stage III non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Anticancer Res, 2018,38(2):885-891. DOI: 10.21873/anticanres.12298.

[12] Takahashi W, Nakajima M, Yamamoto N, et al. A prospective nonrandomized phase I/II study of carbon ion radiotherapy in a favorable subset of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [J]. Cancer, 2015,121(8):1321-1327. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.29195.

[13] Hayashi K, Yamamoto N, Karube M, et al. Prognostic analysis of radiation pneumonitis: carbon-ion radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced lung cancer[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2017, 12(1): 91. DOI: 10.1186/s13014-017-0830-z.

[14] Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(2): 187-199. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71207-0.

[15] Kaster TS, Yaremko B, Palma DA, et al. Radical-intent hypofractionated radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature[J]. Clin Lung Cancer, 2015, 16(2): 71-79. DOI:10.1016/j.cllc.2014.08.002.

[16] Hayashi K, Yamamoto N, Nakajima M, et al. Clinical outcomes of carbon-ion radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Cancer Sci, 2019, 110(2):734-741. DOI: 10.1111/cas.13890.