Heavy Ion Therapy for Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

Heavy Ion Therapy for Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

I. Understanding Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

Most head and neck mucosal melanomas originate from the nasal sinuses and oral cavity, with 70% occurring in the nasal sinuses, 20% in the oral cavity, and 10% in other areas such as the oropharynx and larynx [1,2]. It most commonly occurs between the ages of 50 and 80, and the etiology of mucosal melanoma remains unclear. Epidemiological studies have indicated that smoking, ill-fitting dentures, and the intake/inhalation of carcinogens (including tobacco and formaldehyde) are potential risk factors [3]. Nasal sinus mucosal melanomas often involve the nasal septum and nasal wall, typically presenting with epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and polyps with or without pigmentation. Oral mucosal melanomas frequently involve the upper alveolar ridge and hard palate, often diagnosed incidentally during oral examinations [4]. Persistent nasal bleeding and headaches should raise suspicion for nasal and sinus mucosal melanoma.

II. Treatment of Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

Surgery is the standard treatment for head and neck mucosal melanoma, with complete tumor resection being a key factor in achieving good local control and survival rates. However, due to the proximity of many important organs to the tumor, some patients are not suitable for radical surgery. For those who are inoperable or refuse surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be considered as treatment options. The local control rate (LC) with radiotherapy alone ranges from 0% to 61%, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 13% to 18% [6]. Due to the radioresistant biological characteristics of melanoma, high LET (Linear Energy Transfer) radiation such as neutrons, protons, and carbon ions has received increasing attention. Postoperative radiotherapy is beneficial, with radiation doses as follows: for R0 (margin >5mm) and MDT-recommended postoperative radiotherapy, or R1 (margin 1-5mm): 60Gy/30F; for R2 (margin <1mm): 65Gy/30F. For unresected definitive radiotherapy: radiation dose: 65Gy/30F or equivalent biologically effective dose hypofractionation (each time 2.5-3.0Gy), palliative radiotherapy has a certain role and can be combined with immunotherapy [7].

III. Advantages of Heavy Ion Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

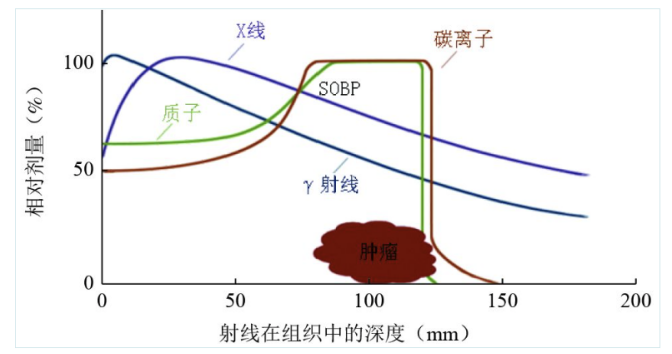

Due to the complex anatomical relationships and the concentration of important organs, surgery is challenging, and the importance and difficulty of preserving organ function are higher than in other tumor sites. In cases where surgical resection is not possible, radiotherapy can still be effective. Conventional radiotherapy uses low LET radiation such as photons (γ-rays, X-rays), and electrons, which exhibit exponential dose attenuation with increasing depth in the body. This results in the absorption of higher doses by surrounding normal tissues compared to deeper tumors, leading to both early and late complications. Carbon ion beams, which are high LET radiation, exhibit a dose reversal at the end of their range, forming a Bragg peak, followed by a sharp drop in dose to zero. During treatment, by adjusting the position of the Bragg peak, the radiation dose can be maximized on the target area, maximizing tumor cell kill while minimizing damage to surrounding normal tissues.

IV. Common Adverse Reactions of Heavy Ion Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

The main adverse reactions of radiotherapy for head and neck mucosal melanoma include oral mucositis, radiation dermatitis, xerostomia, dysgeusia, radiation caries, and radiation-induced osteoradionecrosis. Other complications include dysphagia, hypothyroidism, laryngeal edema, brachial plexus injury, and temporal lobe necrosis. Nearly all (90% -100%) patients with head and neck tumors experience oral mucositis during chemoradiotherapy, and nearly 95% develop radiation dermatitis, presenting as skin erythema, pain, or burning, and desquamation due to dry or moist skin. Xerostomia is very common in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck tumors and is a major factor affecting their quality of life during and after treatment. Patients often complain of dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, or thickened saliva. Dysgeusia refers to taste changes in patients with head and neck tumors during and after radiotherapy. Dysgeusia can occur before the onset of oral mucositis and often precedes xerostomia. Radiation caries refers to tooth decay or tooth loss caused by radiotherapy. Radiation-induced osteoradionecrosis is ischemic necrosis of the bone caused by radiotherapy, usually occurring within the first 3 years after treatment, with the mandible being the most common site, often lasting more than 3 months and slowly worsening without spontaneous healing. In addition to the above adverse reactions, radiotherapy for head and neck tumors may also affect the cornea, lacrimal gland, lens, retina, and optic nerve. Radiation-induced cataracts can be improved by surgical treatment. Lubricants and local antibiotic eye drops can be used to improve keratitis and dry eye syndrome. [8,9,10]The main acute adverse reactions during radiotherapy include oral, nasal mucosal, and skin reactions. For patients requiring irradiation of a large mucosal area, prophylactic placement of a gastric or jejunal feeding tube should be considered, and even gastrostomy before treatment; the correct mouthwash should be chosen to disrupt the bacterial growth environment in the mouth, reduce and inhibit bacterial growth, and maintain oral pH to prevent and control oral infections; after the onset of mucosal reactions, sprays and mouthwashes that promote oral mucosal healing and reduce inflammation can be given at the beginning of treatment. For the prevention of radiation dermatitis, topical skin protectants such as triethanolamine cream and sucralfate can be used non-corticosteroid drugs. Late adverse reactions include dry mouth, localized edema or skin fibrosis of the face and neck

V. Efficacy of Heavy Ion Therapy for Head and Neck Mucosal Malignant Melanoma

For head and neck mucosal malignant melanoma, the prognosis is poor and survival rates are low when the tumor is accompanied by infiltration, necrosis, and vascular involvement. Even with surgery or postoperative combined conventional radiotherapy for nasal, sinus, and nasopharyngeal mucosal melanoma, the 5-year survival rate is only 20% to 30%. If the tumor occurs in the skull base, it often involves the cribriform plate, orbital contents, and dura mater, making surgical treatment not only traumatic but also increasing the risk of iatrogenic metastasis during surgery [11].

Author Institution Efficacy:

| Author | Institution | Curative Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Yanagi et al.[12] | Japan | The 5-year local control rate is 84.1%. |

| Mizoe et al. 等[13] | Japan | The 5-year local control rate is 75%. |

| Naganawa et al. 等 | Japan | The 5-year local control rate, progression-free survival rate, and overall survival rate are 89.5%, 51.6%, and 57.4%, respectively [14]. |

References

[1] Cui C, Lian B, Zhang X, et al. An Evidence-Based Staging System for Mucosal Melanoma: A Proposal. Ann Surg Oncol 2022;29:5221-34.

[2] Mallone S, De Vries E, Guzzo M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of malignant mucosal and uveal melanomas and adnexal skin carcinomas in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1167-75.

[3] Sun S, Huang X, Gao L, et al. Long-term treatment outcomes and prognosis of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: 161 cases from a single institution. Oral Oncol 2017;74:115-22.

[4] Matsuo, M, Rikimaru, F, Higaki, Y, et al. A review of primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Toukeibu Gan 2014; 40 (1): 102-106.

[5] Krengli, M, Masini, L, Kaanders, JH, et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol 2006; 65 (3): 751-9.

[6] Temam, S, Mamelle, G, Marandas, P, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer Am Cancer Soc 2005; 103 (2): 313-9.

[7] Nenclares, P, Ap Dafydd, D, Bagwan, I, et al. Head and neck mucosal melanoma: The United Kingdom national guidelines. Eur J.

[8] Sapir E, Tao Y, Feng F, et al. Predictors of dysgeusia in patients

[9] with oropharyngeal cancer treated with chemotherapy and intensity modulated radiation therapy [J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys,2016,96(2):354-361.

[10] Siddiqui F,Movsas B. Management of radiation toxicity in head andneck cancers[ J]. Semin Radiat Oncol,2017,27(4):340-349.

[11] De Felice F,Musio D, Tombolini V. Osteoradionecrosis and intensi- AL ty modulated radiation therapy: an overview [J].Crit Rev Oncol He-matol, 2016,107:39-43.DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.08.017.

[12] Yanagi, T, Mizoe, JE, Hasegawa, A, et al. Mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck treated by carbon ion radiotherapy. INT J RADIAT ONCOL. 2008; 74 (1): 15-20.

[13] Mizoe, JE, Hasegawa, A, Jingu, K, et al. Results of carbon ion radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. RADIOTHER ONCOL. 2012; 103 RADIOTHER ONCOL. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.12.013

[14] Hayashi K,Koto M,Ikawa H,et al.Feasibility of reirradiation using carbon ions for recurrent head and neck malignancies after carbon ion radiotherapy [J] .Radiother Oncol,2019,136: 148-153.

[15] Masashi K,Yusuke D,JunIchi S,et al.Definitive carbon ion radiation therapy for locally advanced sinonasal malignant tumors:Subgroup analysis of a multicenter study by the Japan Carbon Ion Radiation Oncology Study Group ( J CROS) [ J] .Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys,2018,102(2):353-361.

[16] Hayashi K,Koto M,Ikawa H,et al.Feasibility of reirradiation using carbon ions for recurrent head and neck malignancies after carbon ion radiotherapy [J] .Radiother Oncol,2019,136: 148-153.

[17] Prinzen T ,Klein M ,Hallermann C ,et al.Primary head and neck mucosal melanoma:Predictors of durvival and a case serieson sentinel node biopsy [J] .J Craniomaxillofac Surg,2019,47 (9):1370-1377.

[18] Chinese Society of Radiation Oncology, Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Chinese Society of Radiation Oncology, Chinese Medical Association; Professional Committee of Tumor Radiotherapy, Chinese Anti-Cancer Association. Chinese Guidelines for Radiotherapy of Head and Neck Tumors (2021 Edition) [J]. International Journal of Oncology, 2022(2):65-72.

[19] Guo Wei, Ren Guoxin, Sun Moyi, et al. Expert Consensus on the Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral Mucosal Melanoma in China [J]. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of China, 2021, 19(6):8.

[20] Sun Shiran, Yi Junlin. Current Status and Progress in the Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant Melanoma of the Head and Neck Mucosa [J]. Chinese Journal of Radiation Oncology, 2017, 26(4):4.