MR imaging evaluation of heavy-ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma

MR imaging evaluation of heavy-ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma

Zhao Zhiping, Guan Zhaoyu*, Wang Jianhua, Zhang Yanshan, Wang Huijuan

Department of Radiology, Gansu Wuwei Tumor Hospital, Wuwei 733000, China *

Correspondence to: Guan ZY, E-mail: 343331295@qq.com

Received 5 Dec 2022, Accepted 6 May 2023; DOI: 10.12015/issn.1674-8034.2023.06.005

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Key R&D Program Project of Gansu Province (No. 20YF8FH155).

Cite this article as: ZHAO Z P, GUAN Z Y, WANG J H, et al. MR imaging evaluation of heavy-ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma

[J]. Chin J Magn Reson Imaging, 2023, 14(6): 32-38.

Abstract Objective: To explore the value of MRI in the efficacy evaluation of heavy-ion radiotherapy (HIT) for hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC). Materials and Methods: A retrospective analysis of 25 cases of HCC examed by MRI, compare the axial area, volume and maximum diameter, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), T1WI signal enhancement rate ratio (SER) of the HCC before treatment with the data which after 3-6 months treatment. To evaluate the correlation between the imaging changes and the alpha-fetal protein (AFP) changes. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare changes in AFP, morphological parameters (maximum length, area and volume) and MRI parameters (ADC and SER); Spearman correlation was used to analyze the correlation between the SER of arterial phase (A phase), hepatic portal venous phase (H phase) and venous phase (V phase) and tumor morphology, ADC and tumor marker AFP. Results: The results showed that after HIT, HCC morphology, AFP decreased, and ADC value was significantly increased (P<0.05). Correlation analysis showed that SER of A phase was slightly positively correlated with tumor morphology, and the correlation coefficient with the maximum length and volume of tumor was r=0.29 and r=0.27 (P<0.05), respectively, SER of H phase was also slightly positively correlated with tumor morphology, and the correlation coefficients with area and volume were r=0.28 and r=0.31, respectively (P<0.05), ADC value was negatively correlated with AFP value of tumor marker, and the correlation coefficient was r=-0.40 (P<0.05). The correlation between AFP and tumor size and SER showed that AFP was positively correlated with tumor diameter and volume, r=0.69 and 0.64, respectively (P<0.05). At the same time, AFP was positively correlated with the enhancement rate of A phase, r=0.59 (P<0.05), but not with the enhancement rate of H phase and phase V (P>0.05). Conclusions: HCC changes significantly before and after HIT, and has a good correlation with AFP, with the decrease of AFP, HCC tumor size and SER are decreased which compared with before treatment, while the ADC value is higher than before treatment. MRI can evaluate the efficacy of HIT in HCC effectively.

Key words hepatocellular carcinoma; heavy-ion radiotherapy; efficacy evaluation; diffusion weighted imaging; magnetic resonance imaging

0 Preface

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 75%–85% of liver cancer cases, ranking as the sixth most common cancer globally and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. In Western China, the incidence and mortality rates of liver cancer are the second highest, accounting for 11.88% of all cancer cases and 16% of all cancer deaths [2], with an overall five-year survival rate of 15%–17% [3]. Hepatic resection and liver transplantation are considered radical treatments [4]; however, less than 30% of patients are eligible for surgical intervention at the time of diagnosis [5]. Laparoscopic liver resection is the optimal treatment for patients with solitary HCC (2–5 cm in diameter) and preserved liver function [6]. Most HCC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage and face a poor overall prognosis, primarily due to recurrence and metastasis, which often renders them ineligible for surgery [7].

According to clinical practice guidelines for HCC, transarterial chemoembolization can be used for intermediate-stage HCC, but it is associated with a low necrosis rate. Radiofrequency ablation is effective for treating HCC smaller than 3 cm [8]. With the accumulation of clinical experience in radiotherapy for liver cancer, both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the primary liver cancer diagnosis and treatment standards issued by the National Health Commission of China have recommended radiotherapy as a preferred treatment for unresectable liver cancer or cases where surgery is not feasible [9]. Reported survival times for three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, and particle beam radiotherapy are 5–24 months, 17 months, and 13–22 months, respectively [10]. Heavy-ion therapy (HIT) is a promising cancer treatment method [11] and an emerging radiotherapy technology in recent years. Addressing key clinical issues related to HIT for tumor treatment and developing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that align with the characteristics of HIT is an urgent priority [12].

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels are often elevated in HCC patients, and studies suggest that early changes in AFP may help predict antitumor efficacy in HCC patients [13]. With the continuous advancement of MRI technology, multiparametric imaging has been applied to HCC imaging examinations, significantly improving MRI's capability for early diagnosis and monitoring of HCC. It holds considerable value in prognosis evaluation, treatment selection, efficacy assessment, and monitoring recurrence and metastasis. However, efficacy evaluation currently relies on the maximum tumor diameter per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), while some physicians require measurements of two-dimensional or three-dimensional tumor dimensions, leading to inconsistent standards and requirements. Furthermore, although some HCCs show minimal changes in size and morphology early after treatment, alterations have already occurred at the cellular and molecular levels. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new evaluation methods for effective, accurate, and quantitative assessment of treatment response. There are relatively few studies on using MRI to evaluate the efficacy of heavy-ion therapy (HIT) for HCC. This study aims to supplement data on functional MRI parameters—such as the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and the signal enhancement ratio (SER) on dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging—in the context of HIT for HCC. By combining these with AFP levels and conducting correlation analyses, we seek to validate the accuracy and reliability of these methods for assessing HIT efficacy in HCC.

1 Materials and Methods

1.1 Study Subjects

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Wuwei Cancer Hospital, with a waiver of informed consent (Approval No.: 2018-ETHICAL REVIEW-21). A retrospective analysis was conducted on 25 HCC cases treated with heavy-ion therapy (HIT) between November 2018 and August 2022.

Inclusion criteria:

(1) Pathologically or radiologically (CT/MRI) diagnosed with HCC;

(2) All patients underwent HIT;

(3) Complete MRI data before and after HIT treatment with accurate measurements.

Exclusion criteria:

(1) Patients who did not complete the full course of treatment;

(2) Tumors <1 cm or with extensive cystic necrosis (lesions with contrast uptake on MRI enhancement showing a transverse diameter <1 cm);

(3) Patients receiving combined chemotherapy or other treatments.

1.2 Scanning Equipment and Methods

This study compared the axial area, volume, maximum diameter, and ADC values of tumors before treatment and at the 3–6 month follow-up after treatment. All patients underwent the following MRI examinations before treatment and at the 3–6 month follow-up after treatment. A German Siemens 3.0 T Skyra superconducting MRI scanner with a 16-channel abdominal coil was used. Plain scan: Coronal T2WI sequence was performed with parameters: spin echo (SE) sequence, TR 1800 ms, TE 87 ms, FOV 420 mm × 420 mm, slice thickness 5 mm, spacing 1 mm, covering the entire liver. Axial T1WI: Dixon sequence was used to obtain four sets of images: in-phase, out-of-phase, fat-phase, and water-phase. Parameters: gradient echo (GRE) sequence, TR 4 ms, TE 2 ms, FOV 400 mm × 325 mm, slice thickness 5 mm, spacing 1 mm, covering the entire liver. T2WI scan: Parameters: fat suppression (FS) sequence, TR 3957 ms, TE 84 ms, FOV 300 mm × 256 mm, slice thickness 5 mm, spacing 1 mm, covering the entire liver. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) was then performed, and ADC images were reconstructed. Parameters: echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence, TR 6800 ms, TE 48 ms, FOV 380 mm × 306 mm, b-values 50, 400, 800 s/mm², slice thickness 5 mm, spacing 1 mm. Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging used T1WI 3D volumetric interpolated technique. Parameters: gradient echo (GRE) sequence, TR 4 ms, TE 1 ms, FOV 400 mm × 325 mm, slice thickness 3 mm, spacing 0 mm. The contrast agent GD-DTPA (gadopentetate dimeglumine injection, Kangchen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) was administered via rapid intravenous bolus using a high-pressure injector at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg and a flow rate of 2 mL/s. A total of 4 scans were performed: at 15 s, 20 s, 50–60 s, and 3–5 min after injection, corresponding to early arterial phase (A phase), late arterial phase (A phase), hepatic portal venous phase (H phase), and venous phase (V phase) images, respectively.

1.3 Image Analysis

Two physicians (one attending physician with 20 years of imaging diagnostic experience and one associate chief physician with 29 years of experience) measured the axial area, volume, and maximum diameter of the tumors before and after treatment on T1WI enhanced sequences using a Siemens MRWP workstation. They also measured the ADC values in diffusion-restricted areas on DWI with a b-value of 800 s/mm², and calculated the signal enhancement ratio (SER) for the three phases (A phase, H phase, and V phase) using the formula: SER = (SIpost - SIpre) / SIpre × 100%, where SIpre and SIpost represent the signal intensity before and after enhancement, respectively. When tumor signal heterogeneity was observed, three measurements were taken and averaged. In case of disagreement between measurements, the result from the higher-ranked physician was adopted. Regions of interest (ROIs) were delineated on the axial slice showing the largest tumor area, carefully avoiding hemorrhage, necrotic tissue, and vascular regions.

1.4 Serological Testing and Efficacy Evaluation

Serum AFP concentration was measured using radioimmunoassay, with a normal reference value of ≤5.8 IU/mL. The correlations between changes in tumor morphology (area, volume, maximum diameter), ADC values, three-phase SER, and AFP levels were evaluated.

1.5 Heavy-Ion Therapy

HIT was delivered using a medical heavy-ion accelerator developed by the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Lanzhou) (TPS version V1.0, Lanzhou Kejintaiji New Technology Co., Ltd.). The prescribed radiation dose was fixed at 64–76 Gy (RBE), with strict dose constraints for organs at risk.

1.6 Statistical Analysis Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. Comparisons of AFP levels, morphological parameters (maximum diameter, area, volume), and functional MRI parameters (ADC, SER) before and after treatment were conducted using paired Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, with normality tests performed on the data prior to analysis. Spearman correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships between triphasic SER on T1WI-enhanced imaging and tumor morphology, ADC values, and AFP levels.

For clinical characteristics:

• Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared between groups using t-tests.

• Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

• Categorical variables were described as frequency (percentage) and compared using chi-square tests (with continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate).

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

1.7 Follow-up

Active follow-up was conducted primarily via telephone to collect patients' post-treatment imaging data and survival status, with a follow-up interval of 3 to 6 months after treatment.

2 Result

2.1 Case Enrollment Results

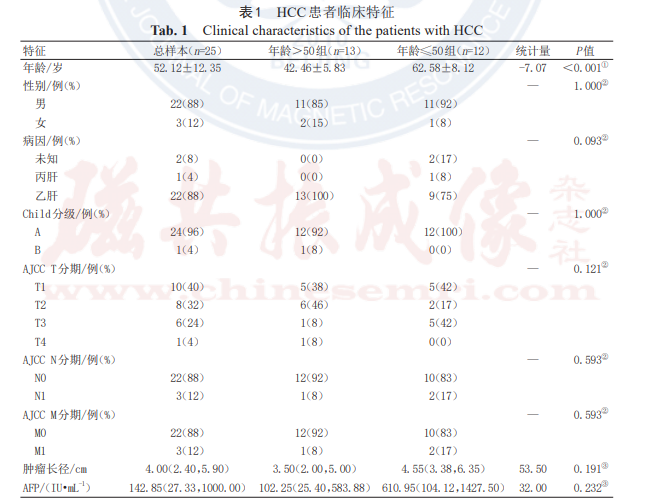

The study ultimately enrolled 25 HCC patients, including 22 males and 3 females, aged 32–75 years (mean 53.08 ± 11.32 years). All 25 HCC patients completed HIT treatment as scheduled. Except for age, no statistically significant differences were observed in the general clinical characteristics of the patients (P > 0.05), as detailed in Table 1.

Note: HCC denotes hepatocellular carcinoma; Child-Pugh classification is a grading system for quantitatively assessing liver reserve function in patients with cirrhosis; AJCC refers to the American Joint Committee on Cancer; AFP denotes alpha-fetoprotein.

① Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and intergroup differences were analyzed using t-tests;

② Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage), and intergroup differences were analyzed using chi-square tests;

③ Non-normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as median (upper and lower quartiles), and intergroup differences were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

2.2 Measurement Data Consistency

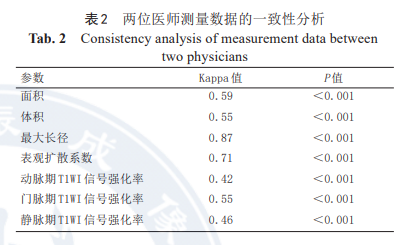

The measurements of tumor morphological parameters (area, volume, maximum diameter) and MRI functional parameters (ADC, triphasic SER) before and after HIT treatment by both physicians showed good consistency, as detailed in Table 2.

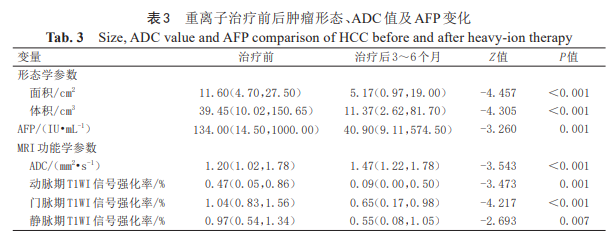

2.3 Changes in Tumor Size, ADC Values, and AFP Levels Before and After HIT Treatment

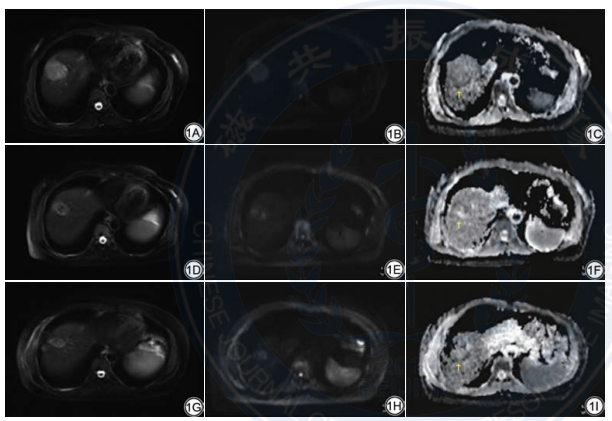

The paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-parametric paired test) results for AFP, morphological parameters (maximum diameter, area, volume), and MRI functional parameters (ADC, SER) before and after treatment showed that HCC morphology significantly shrunk and AFP levels markedly decreased after therapy. Concurrently, SER values significantly decreased while ADC values significantly increased (all P < 0.05). For details, refer to Table 3 and Figure 1.

Note: ADC denotes apparent diffusion coefficient; AFP denotes alpha-fetoprotein; HCC denotes hepatocellular carcinoma. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range).

Fig. 1 Female, 49 years old, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is diagnosed histologically by percutaneous biopsy. Changes in tumor size and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value before and after heavy-ion therapy (HIT) treatment with HCC. 1A: Before treatment, axial of T2WI shows a slight high signal mass in the right lobe of the liver, which is about 4.2 cm×3.8 cm×4.8 cm in size; 1B: Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) shows diffuse limitation; 1C: ADC value (b=800 s/mm²) is 0.83 mm2 /s; 1D: The signal of the tumor is mixed and long T2 after 1 months of treatment, the size is about 2.7 cm×2.3 cm×3.9 cm; 1E: DWI shows diffuse limitation; 1F: ADC value (b=800 s/mm²) is 0.65 mm2/s; 1G: The signal of the tumor is mixed and long T2 after 5 months of treatment, the size of tumor is about 2.2 cm×2.0 cm×2.6 cm; 1H: DWI shows diffuse limitation; 1I: ADC value (b=800 s/mm²) is 1.11 mm2/s.

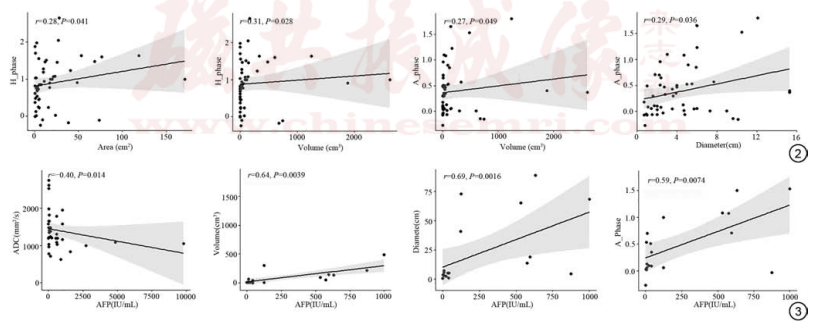

Fig. 2 Correlation of SER and tumor morphology. Fig. 3 Correlation of diffusion weighted imaging ADC values, size and SER of HCC with AFP. SER: signal enhancement ratio; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; AFP: alpha-fetal protein; H phase: the SER of T1WI in hepatic portal phase dynamic enhanced scanning; A phase: the SER of T1WI in hepatic arterial phase dynamic enhancement scanning.

2.4 Correlation Between MRI Functional Quantitative Parameters and Morphology/Tumor Marker AFP

Spearman correlation analysis showed that the SER in the A phase was mildly positively correlated with tumor morphology (P < 0.05), indicating that as the tumor shrank, its enhancement degree decreased. The correlation coefficients with tumor volume and maximum diameter were 0.27 and 0.29, respectively (Figure 2). The SER in the H phase was also mildly positively correlated with tumor morphology (P < 0.05), with correlation coefficients of 0.28 and 0.31 for area and volume, respectively (Figure 2). The ADC value was negatively correlated with the tumor marker AFP (r = -0.40, P < 0.05), meaning that as the ADC value increased, the AFP value decreased (Figure 3). AFP was positively correlated with tumor volume and diameter (r = 0.64 and 0.69, respectively, both P < 0.05). Additionally, AFP was positively correlated with the SER in the A phase (r = 0.59, P < 0.05) (Figure 3), but showed no significant correlation with the SER in the H and V phases (P > 0.05).

2.5 Follow-up After Treatment

The median follow-up period in this study was 3–6 months. Among the 25 patients, although the primary lesions shrank in 2 cases after treatment, one developed lung metastasis after 6 months, and the other developed liver metastasis at 9.5 months. Additionally, despite shrinkage of the primary lesions in another 2 cases, one died of liver failure at 10 months post-treatment, and the other died of gastrointestinal bleeding at 12 months post-treatment.

3 Discussion

This study utilized multiparametric MRI to measure the axial area, volume, maximum diameter, ADC values, and triphasic (A phase, H phase, V phase) SER of HCC tumors. It compared the differences in these parameters before and after HIT treatment, analyzed the correlation between such imaging changes and AFP variations, and evaluated the value of MRI in efficacy assessment. The results demonstrated significant reduction in HCC size and decreased AFP levels after HIT treatment. Concurrently, the functional MRI quantitative parameters—triphasic SER—showed significant decreases, while ADC values significantly increased (all P < 0.05). Correlation analysis revealed mild positive correlations between arterial phase (A phase) SER and tumor morphology, as well as between portal venous phase (H phase) SER and tumor morphology. ADC values were negatively correlated with AFP levels. Studies on the relationship between AFP and tumor size/SI indicated positive correlations between AFP and both tumor diameter and volume (all P < 0.05). Additionally, AFP was positively correlated with arterial phase (A phase) enhancement rate but showed no significant correlation with portal venous phase (H phase) or venous phase (V phase) enhancement rates (P > 0.05).

Accurate and effective evaluation of the efficacy of heavy-ion therapy (HIT) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is clinically crucial. While CT and ultrasound techniques can assess treatment response based on morphological features, functional MRI provides more detailed radiological characteristics of HCC post-treatment, revealing diverse imaging manifestations. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the correlation between changes in tumor morphology, ADC values, and signal enhancement ratio (SER) before and after HIT treatment alongside AFP dynamics, enabling a quantitative analysis of HIT efficacy for HCC. This approach is more innovative than previously reported methods involving interventional or chemotherapy for HCC, and offers a more comprehensive and specific assessment compared to studies relying solely on ADC values or T1WI enhancement amplitude, demonstrating superior clinical applicability.

3.1 Advantages of HIT in Liver Cancer Treatment

HIT demonstrates significant efficacy in treating liver cancer, characterized by the following features:

(1) Precise dose distribution: Heavy-ion beams belong to high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation [14]. Upon entering tissue, they initially exhibit a plateau region followed by a sharp peak of energy deposition—the Bragg peak—where energy is fully released at the end of their range. Unlike conventional X-rays, heavy ions exhibit far higher LET within the Bragg peak region, enabling concentrated energy delivery to cover the tumor volume. This maximizes tumor cell destruction while minimally affecting tissues beyond the target [15].

(2) Superior biological effectiveness: The relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of heavy-ion radiotherapy is 2–5 times higher than that of protons or photons. Heavy ions directly damage DNA molecules, causing double-strand breaks that are difficult to repair, and remain effective even against hypoxic tumor cells [16]. A Japanese prospective clinical study of HIT for liver cancer reported that among 124 treated patients, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year local control rates were 94.7%, 91.4%, and 90.0%, respectively, while overall survival rates were 90.3%, 50.0%, and 25.0%. Nearly no severe adverse effects were observed [17]. HIT achieves high local control rates with low toxicity in clinical practice [18]. Its advantages are particularly evident in elderly patients, those with multiple comorbidities, complex lesion anatomy, or surgical challenges—such as tumors adjacent to bile ducts, blood vessels, or the hepatic hilum—where other ablation techniques (e.g., radiofrequency or cryoablation) are infeasible [19]. Shiba et al. [20] suggested that the primary pattern of recurrence after HCC treatment is intrahepatic relapse outside the irradiated field, and the main cause of death is related to HCC progression. The high rate of intrahepatic recurrence outside the treatment zone may be attributed to pre-existing micrometastases undetectable by imaging or difficulties in defining true tumor boundaries in cirrhotic livers. Literature reports indicate that the incidence of severe adverse events (≥ Grade 3) after HIT for HCC is very low, with no treatment-related deaths [21], which aligns with our follow-up findings.

3.2 Changes in ADC Values of HCC Before and After HIT

MRI demonstrates excellent tissue and spatial resolution, enabling clear visualization of the relationship between liver cancer and surrounding tissues, playing a critical role in both diagnosis and therapeutic efficacy assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [22]. Studies indicate that simplified non-contrast MRI (sensitivity 86%, specificity 94%) performs comparably to contrast-enhanced scans (sensitivity 87%, specificity 94%) in detecting HCC, while ultrasound exhibits lower sensitivity than simplified MRI (53% vs. 82%) [23]. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is a technique reflecting tissue microstructural composition. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) quantifies the random motion of water molecules within tissues [24]. A higher ADC value indicates faster water molecule diffusion. Increased cellular density and expanded volume in tumor tissue, along with heterogeneity in intracellular fibrous matrices and organelles, restrict water molecule diffusion, resulting in reduced ADC values. Moreover, highly active tumor cells with intact membranes further limit water movement, leading to decreased ADC; conversely, ADC values rise when these conditions reverse [25]. The clinically detectable or exam-verified tumor extent is defined as maximum tumor volume, whose size positively correlates with tumor cell count [26]. A favorable treatment response is defined as ≥30% reduction in the sum of diameters of enhanced lesions post-therapy, while <30% reduction indicates treatment failure [27]. This study employed one-dimensional (maximum diameter), two-dimensional (axial area), and three-dimensional (tumor volume) measurements, using pre-HIT treatment data as baseline. Compared to tumor size at 3–6 months post-treatment follow-up, lesions showed continuous shrinkage with statistically significant differences (P<0.05), all meeting RECIST criteria for stable disease or partial response [28]. Some studies conducted comparative DWI analysis pre- and post-treatment, supplemented by surgical and pathological examination of tumor tissue. Pathological results revealed higher ADC values in necrotic tumor regions (liquefactive necrosis) than in viable tissue, suggesting ADC can specifically distinguish necrotic tumors from living cells. Patients achieving complete response after initial therapy showed a trend of increased ADC values compared to those requiring secondary surgery. ADC evaluation also aids in predicting treatment response [29]. SHAGHAGHI et al. [30] proposed that changes in mean ADC and ADC kurtosis can predict overall survival in well-defined HCC, monitor early response to transarterial chemoembolization, and identify patients with treatment failure or suboptimal outcomes. Research shows that despite short-term volume increase (possibly due to cellular edema) post-treatment for colorectal liver metastases, ADC values rise—a change absent in untreated metastases [31]. Other reports note significantly elevated ADC values in HCC lesions with successful embolization outcomes. Post-treatment, higher ADC values correlate with lower progression or mortality rates compared to low ADC values [32]. The extent of ADC changes correlates with overall survival, even preceding anatomical changes [1]. In this study, comparing baseline ADC values pre-HIT to post-treatment follow-up at b=800 s/mm², ADC increased from 1.20 mm²/s to 1.47 mm²/s, with statistical significance (P<0.05).

3.3 Changes in SER of HCC Before and After HIT

The enhancement patterns of the liver across different phases are attributed to its dual blood supply. Normally, approximately 70% of hepatic blood flow derives from the portal vein, while 30% comes from the hepatic artery. In contrast, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) primarily relies on the hepatic artery for blood supply, exhibiting enhancement before the portal venous phase and washout thereafter [33]. This enhancement pattern correlates with the degree of tumor cell differentiation and histological type of HCC. Studies indicate that the number of unpaired hepatic arteries increases during the progression from well-differentiated to moderately differentiated HCC, but decreases during the transition from moderately to poorly differentiated HCC. Consequently, some poorly differentiated HCCs and those with portal venous supply show reduced arterial blood flow, leading to altered perfusion during arterial and portal venous phases and a consequent decrease in quantitative parameters [34]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) involves intravenous injection of low-molecular-weight gadolinium-based contrast agents. The contrast agent distributes from blood vessels into tissues, shortening longitudinal relaxation times and thereby increasing signal intensity (SI) on T1-weighted images. The SI measured on DCE-MRI reflects a combination of permeability and perfusion changes. Such perfusion-related signal alterations have been demonstrated to correlate with tumor angiogenesis [35]. The signal enhancement ratio (SER) semi-quantitatively reflects changes in tissue enhancement. In this study, SER was used to quantify perfusion-related signal intensity changes in HCC before and after enhancement, thereby evaluating DCE-MRI performance pre- and post-treatment. Our findings revealed that SER values significantly decreased (P < 0.05) at 3–6 months post-heavy-ion therapy (HIT) compared to pre-treatment levels, indicating that after HIT, tumor enhancement degree and blood supply were markedly reduced due to apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells.

3.4 Correlation Between AFP and MRI Multiparameters in HCC Before and After HIT

Detection of AFP not only aids in the diagnosis of primary liver cancer but also serves as a criterion for evaluating treatment efficacy [36]. DUVOUX et al. [37] suggested that AFP levels can predict tumor recurrence and are associated with vascular invasion and differentiation. Some reports indicate that higher AFP levels after HCC treatment may correlate with early recurrence of HCC [38]. This study found that after HIT treatment, AFP levels decreased compared to pre-treatment values. Using the change in AFP before and after treatment as a reference, we evaluated the correlation between changes in tumor size, ADC values, and SER with AFP alterations following HIT for HCC. The results showed that changes in lesion size and SER were positively correlated with changes in AFP, meaning that as lesions shrank and enhancement decreased, AFP levels also declined. In contrast, changes in ADC values were negatively correlated with changes in AFP, indicating that as AFP decreased, lesion ADC values increased (all P < 0.05).

3.5 Limitations of This Study

Firstly, due to temporal and geographical constraints, some patients returned to their places of origin for follow-up examinations after treatment, resulting in difficulties in data collection and a limited sample size. In future studies, we will continue to accumulate data to expand the sample size. Secondly, when comparing tumor volumes, the inter-slice spacing was not taken into account. Additionally, due to individual circulatory differences, the homogeneity of triple-phase MRI images across patients was limited, which may have influenced the statistical results to some extent. Thirdly, the limitations of using AFP alone to evaluate therapeutic efficacy were not fully considered. In future research, we will combine AFP with other tumor markers to further analyze their correlation with treatment response. Lastly, the follow-up period in this study was overly extended. For mid-to-late stage treatment assessment, standards such as survival rate and response rate should be adopted to evaluate tumor treatment outcomes, which will also be a focus of our future research.

4 Conclusion

In summary, MRI parameters such as HCC tumor size, SER, and ADC values can noninvasively evaluate the efficacy of HIT treatment, tumor cell activity level, and necrosis in HCC. This approach provides an alternative assessment method beyond the size-based RECIST 1.1 criteria and can guide clinical practice in radiotherapy for liver cancer. These findings hold significant guidance value for clinicians in determining subsequent treatment steps and follow-up strategies.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship Contribution Statement: Guan Zhaoyu participated in the topic selection and design of this study, revised critical content of the manuscript, and obtained funding from the Gansu Provincial Key R&D Program; Zhao Zhiping drafted and wrote the manuscript, acquired, analyzed, or interpreted the data of this study; Wang Jianhua participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, collected, organized, and analyzed the data; Zhang Yanshan and Wang Huijuan collected, organized, and analyzed the data, and revised key content of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for publication and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the research.

References

[1] QAYUM K, KAR I, RASHID U, et al. Effects of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation on hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a SEER-based study[J/OL]. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2021, 69: 102782[2023-03-20]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2049080121007329. DOI: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102782.

[2] ZHENG R S, QU C F, ZHANG S W, et al. Liver cancer incidence and mortality in China: temporal trends and projections to 2030[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2018, 30(6): 571-579. DOI: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.06.01.

[3] RAO C V, ASCH A S, YAMADA H Y. Frequently mutated genes/pathway sand genomic instability as prevention targets in liver cancer[J].Carcinogenesis, 2017, 38(1): 2-11. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/bgw118.

[4] WANG H L, MO D C, ZHONG J H, et al. Systematic review of treatment strategy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: salvage liver transplant ationor curative locoregional therapy[J/OL]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2019, 98(8):e14498 [2022-08-24]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6408068. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014498.

[5] SUGAWARA Y. Living-donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: current situations and challenge[J/OL].Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2020, 19(1): 11-12. [2022-11-28]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1499387219302504?via%3Dihub. DOI: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.11.009.

[6] ZHANG Y X, PEI Y L, CHEN X P, et al. Treatment for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma ranging from 2 and 5 cm: is the curative effect ofno-touch multibipolar radiofrequency ablation comparable to that of surgical resection?[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(3): 575-576. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.039.

[7] FAN Y H, LIU M. The potential role of SEPT6 in liver fibrosis andhuman hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Arch Med Res, 2020, 1(1): 22-25.DOI: 10.33696/Gastroenterology.1.005.

[8] XU Z T, XIE H Y, ZHOU L, et al. The combination strategy oftransarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation or microwaveablation against hepatocellular carcinoma[J/OL]. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst),2019, 2019: 8619096 [2022-08-17]. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/acp/2019/8619096/. DOI: 10.1155/2019/8619096.

[9] 国家卫生健康委办公厅 . 原发性肝癌诊疗指南(2022 年版)[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2022, 38(2): 288-303. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.02.009.General Office of National Health Commission. Standardization fordiagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2022 edition)[J].J Clin Hepatol, 2022, 38(2): 288-303. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.02.009.

[10] GALLE P R, TOVOLI F, FOERSTER F, et al. The treatment ofintermediate stage tumours beyond TACE: from surgery to systemictherapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2017, 67(1): 173-183. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.007.

[11] GOETZ G, MITIĆ M, MITTERMAYR T, et al. OP157 Carbon Ion Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review[J]. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 2019, 35(S1): 34-35. DOI: 10.1017/S0266462319001740.

[12] 刘锐锋, 张秋宁, 田金徽, 等 . 重离子治疗在肿瘤治疗中的临床应用及前景展望[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2021, 30(8): 619-626. DOI: 10.11735/j. issn.1004-0242.2021.08.A008. LIU R F, ZHANG Q N, TIAN J H, et al. Application and prospect of heavy ion therapy in cancer treatment[J]. China Cancer, 2021, 30(8): 619-626. DOI: 10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2021.08.A008.

[13] KUZUYA T, KAWABE N, HASHIMOTO S, et al. Early changes in alpha-fetoprotein are a useful predictor of efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Oncology, 2022, 100(1): 12-21. DOI: 10.1159/000519448.

[14] WEBER U A, SCIFONI E, DURANTE M. FLASH radiotherapy with carbon ion beams[J]. Med Phys, 2022, 49(3): 1974-1992. DOI: 10.1002/

mp.15135.

[15] MÜNCHMEYER M, SMITH K M. Higher N-point function data analysis techniques for heavy particle production and WMAP results[J/ OL]. Phys Rev D, 2019, 100(12): 123511 [2022-08-05]. https://sci-hub. st/10.1103/PhysRevD.100.123511. DOI: 10.1103/physrevd.100.123511.

[16] RACKWITZ T, DEBUS J. Clinical applications of proton and carbon ion therapy[J]. Semin Oncol, 2019, 46(3): 226-232. DOI: 10.1053/j.

seminoncol.2019.07.005.

[17] KASUYA G, KATO H, YASUDA S, et al. Progressive hypofractionated carbon-ion radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: combined analyses of 2 prospective trials[J]. Cancer, 2017, 123(20): 3955-3965. DOI: 10.1002/ cncr.30816.

[18] HAYASHI K, YAMAMOTO N, NAKAJIMA M, et al. Clinical outcomes of carbon-ion radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Cancer Sci, 2019, 110(2): 734-741. DOI: 10.1111/ cas.13890.

[19] SHIBA S, ABE T, SHIBUYA K, et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy for 80 years or older patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J/OL]. BMC

Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 721 [2022-07-30]. https://sci-hub.et-fine.com/10.1186/ s12885-017-3724-4. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-017-3724-4.

[20] SHIBA S, SHIBUYA K, KATOH H, et al. No deterioration in clinical outcomes of carbon ion radiotherapy for sarcopenia patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Anticancer Res, 2018, 38(6): 3579-3586. DOI: 10.21873/anticanres.12631.

[21] 邵丽华, 张秋宁, 罗宏涛, 等. 碳离子和质子治疗肝细胞癌的Meta分析[J]. 肿瘤防治研究, 2020, 47(5): 358-366. DOI: 10.3971/j.issn.1000-

8578.2020.19.1158. SHAO L H, ZHANG Q N, LUO H T, et al. Carbonions and proton therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Res Prev Treat, 2020, 47(5): 358-366. DOI: 10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2020.19.1158.

[22] ZHENG C F, CHEN L, JIAN J H, et al. Efficacy evaluation ofinterventional therapy for primary liver cancer using magneticresonance imaging and CT scanning under deep learning and treatmentof vasovagal reflex[J].J Supercomput, 2021, 77(7): 7535-7548. DOI:10.1007/s11227-020-03539-w.

[23] GUPTA P, SOUNDARARAJAN R, PATEL A, et al. Abbreviated MRIfor hepatocellular carcinoma screening: a systematic review andmeta-analysis[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 75(1): 108-119. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.041.

[24] MEYER H J, ZIEMANN O, KORNHUBER M, et al. Apparentdiffusion coefficient (ADC) does not correlate with different serologicalparameters in myositis and myopathy[J]. Acta Radiol, 2018, 59(6):694-699. DOI: 10.1177/0284185117731448.

[25] CHOI Y J, LEE I S, SONG Y S, et al. Diagnostic performance ofdiffusion-weighted (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRIfor the differentiation of benign from malignant soft-tissue tumors[J]. JMagn Reson Imaging, 2019, 50(3): 798-809. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.26607.

[26] ZHAO D, HU Q Q, QI L P, et al. Magnetic resonance (MR) imagingfor tumor staging and definition of tumor volumes on radiationtreatment planning in nonsmall cell lung cancer[J/OL]. Medicine,2017, 96(8): e5943 [2022-08-17]. https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/pages/default.aspx. DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000005943.

[27] AHMED E I, HASSAN M S, ABDEL-MUTALEB M G, et al. The roleof diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging and subtractionmagnetic resonance imaging in assessing treatment response ofhepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization[J].Egypt J Hosp Med, 2018, 72(3): 4165-4174. DOI: 10.21608/ejhm.2018.9133.

[28] LITIÈRE S, COLLETTE S, DE VRIES E G E, et al. RECIST—learning from the past to build the future[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017,14(3): 187-192. DOI: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.195.

[29] OGIWARA H, TSUTSUMI Y, MATSUOKA K, et al. Apparentdiffusion coefficient of intracranial germ cell tumors[J].J Neuro Oncol,2015, 121(3): 565-571. DOI: 10.1007/s11060-014-1668-y.

[30] SHAGHAGHI M, ALIYARI GHASABEH M, AMELI S, et al.Post-TACE changes in ADC histogram predict overall and transplant-freesurvival in patients with well-defined HCC: a retrospective cohort with upto 10 years follow-up[J]. Eur Radiol, 2021, 31(3): 1378-1390. DOI:10.1007/s00330-020-07237-2.

[31] KATHARINA INGENERF M, KARIM H, FINK N, et al. Apparentdiffusion coefficients (ADC) in response assessment of transarterialradioembolization (TARE) for liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumors(NET): a feasibility study[J]. Acta Radiol, 2022, 63(7): 877-888. DOI:10.1177/02841851211024004.

[32] NIEKAMP A, ABDEL-WAHAB R, KUBAN J, et al. Baseline apparent diffusion coefficient as a predictor of response to liver-directedtherapies in hepatocellular carcinoma[J/OL]. J Clin Med, 2018, 7(4):83 [2022-08-17]. https://sci-hub.ee/10.1002/cncr.30816. DOI: 10.3390/jcm7040083.

[33] BOAS F E, KAMAYA A, DO B, et al. Classification of hypervascularliver lesions based on hepatic artery and portal vein blood supply coefficients calculated from triphasic CT scans[J]. J Digit Imaging,2015, 28(2): 213-223. DOI: 10.1007/s10278-014-9725-9.

[34] SHAO C C, ZHAO F, YU Y F, et al. Value of perfusion parameters and histogram analysis of triphasic computed tomography in pre-operative prediction of histological grade of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. ChinMed J (Engl), 2021, 134(10): 1181-1190. DOI: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001446.

[35] CHEN B B, SHIH T T. DCE-MRI in hepatocellular carcinoma-clinical and therapeutic image biomarker[J/OL]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014,20(12): 3125 [2022-11-28]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3964384. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3125.

[36] 刘胜荣, 刁平, 黄晓红. AFP在原发性肝癌组织和血清中的表达与临床、病理的相关性研究[J]. 中国肿瘤外科杂志, 2012, 4(4): 223-226.DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4136.2012.04.010.LIU S R, DIAO P, HUANG X H. Correlation research of AFPexpression in liver cancer tissue and serum with clinicopathologicalcharacteristics[J]. Chin J Surg Oncol, 2012, 4(4): 223-226. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4136.2012.04.010.

[37] DUVOUX C, ROUDOT-THORAVAL F, DECAENS T, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model includingα-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria[J/OL].Gastroenterology, 2012, 143(4): 986-994. e3 [2022-11-28]. https://sci-hub.et-fine.com/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.011. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.011.

[38] WATANABE T, TOKUMOTO Y, JOKO K, et al. AFP and eGFR are related to early and late recurrence of HCC following antiviral therapy[J/OL]. BMC Cancer, 2021, 21(1): 699 [2023-03-10]. https://sci-hub.et-fine.com/10.1186/s12885-021-08401-7. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-021-08401-7.