Dunhuang: A Civilization Sanctuary in the Desert

The name "Dunhuang" speaks of grandeur—"Dun" meaning vast, "Huang" meaning glorious. This magnificent oasis, resplendent with awe-inspiring murals that transcend time, carries the civilization and wisdom of the Chinese nation. A radiant pearl in the boundless desert, it has captivated generations of artists. Today, from physical tourism to virtual exhibitions, from the "Flying Apsaras of Dunhuang" in Olympic rhythmic gymnastics to classroom-break "Dunhuang dance" routines, from exquisite museum文创 (cultural creative products) to everyday clothing and food—Dunhuang culture, tempered by millennia, continues to shine with undiminished brilliance.

Dunhuang, the westernmost oasis city of the Hexi Corridor, remains an undying jewel on the Silk Road. Over two thousand years ago, as a strategic stronghold for the Han Empire's expansion into the Western Regions, it witnessed the most radiant collisions and fusions of Eastern and Western civilizations. The thousand-year Buddhist radiance of the Mogao Caves, the natural wonder of the Singing Sand Mountains, and the poetic frontier spirit of the Yangguan and Yumen Passes together weave the very soul of this desert city.

一、Introduction

Nestled in the northwestern reaches of Gansu Province at the western terminus of the Hexi Corridor, Dunhuang spans 31,200 square kilometers along the eastern fringe of the Kumtag Desert, positioned at 40°N latitude and 94°E longitude. Framed by the Sanwei Mountains—an offshoot of the Qilian Range—to the south and bordering the Gobi Desert with views toward Hami, Xinjiang to the north, the Dang River carves through the arid landscape, sustaining this vital desert oasis.

Since its establishment as Dunhuang Commandery in 111 BC during Emperor Wu of Han's reign, the city has served as the "throat and key" of the Silk Road. A mandatory passageway for Buddhism's eastward spread and merchant caravans' westward journeys, it became a melting pot where four great civilizations—Chinese, Indian, Greek, and Islamic—converged, forging its legacy as "the cosmopolitan hub where all peoples gathered."

Mogao Caves: A Millennial Sanctuary of Buddhist Art on the Silk Road

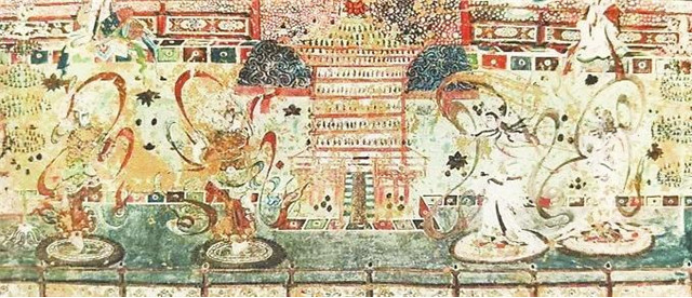

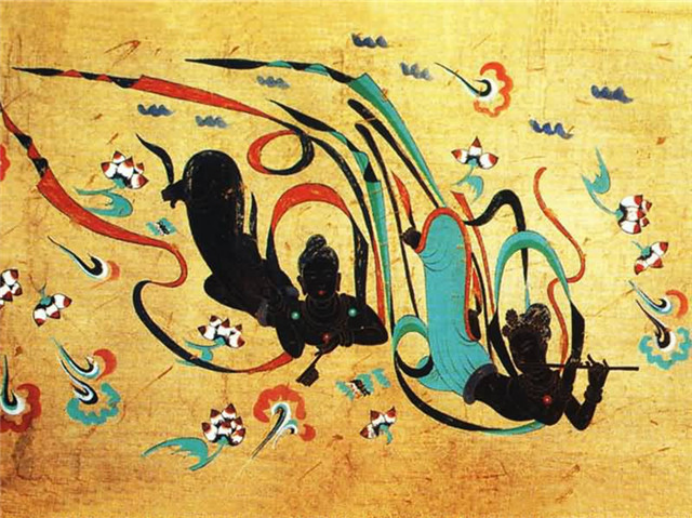

Carved into the cliffs of the Singing Sand Mountains 25 kilometers southeast of Dunhuang, the Mogao Caves were first excavated in 366 AD during the Former Qin dynasty. Over ten successive dynasties from the Sixteen Kingdoms period to the Yuan dynasty, this sacred complex grew into the world's largest and most comprehensive treasury of Buddhist art, now preserving 735 caves, 45,000 square meters of murals, and 2,415 painted sculptures.

Within these grottoes lies an uninterrupted artistic legacy spanning the 4th to 14th centuries: the Northern Wei period's "elegant figures with refined bones" reveal Central Asian painting styles, Tang dynasty sutra illustrations embody golden-age grandeur, while Western Xia's Green Tara murals synthesize Tibetan Buddhist elements. The accidental 1900 discovery of the Library Cave yielded over 50,000 manuscripts in Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur and other scripts, giving birth to the international academic discipline of "Dunhuangology."

From the 35-meter-tall Maitreya Buddha in Cave 96 to the legendary Library Cave (Cave 17) and the Zhenguan-era murals in Cave 220, every detail narrates Buddhism's eastward journey and sinicization. Now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this artistic pantheon employs digital preservation to immortalize its millennia-old masterpieces, continuing to tell the Silk Road's most captivating tales of cross-civilizational dialogue.

Dance and Music" - Mogao Cave 220, Early Tang Dynasty

Murals from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang

Set against the backdrop of Dunhuang's rich cultural heritage, this epic love story transcends a thousand years. The young painter Mo Gao, in his quest for artistic perfection, journeys to Dunhuang. On the verge of death during his travels, he is saved by a woman named Crescent Moon. When the two reunite in Dunhuang, love blossoms—only to be met with fierce opposition from Crescent Moon's father, a powerful general. In the end, Crescent Moon sacrifices her life to protect Mo Gao, her spirit transforming into a clear spring. With its waters moistening his brush, Mo Gao completes his artistic masterpiece, a final testament to their love.

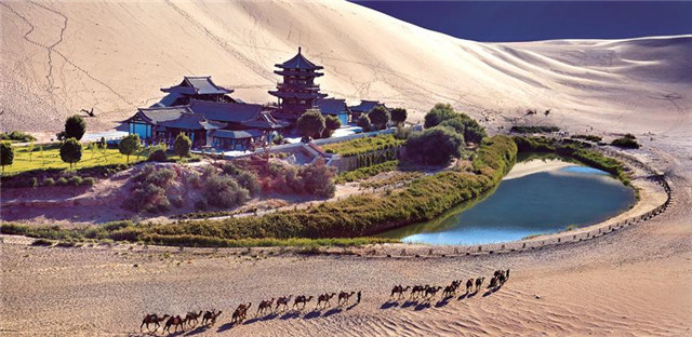

The Singing Sand Dunes and Crescent Moon Spring: A Natural Marvel in the Gobi Desert

Five kilometers south of Dunhuang city, amidst a golden sea of sand, the Singing Sand Dunes and Crescent Moon Spring perform nature's eternal miracle—where "mountains and springs coexist, sand and water thrive together." Stretching 40 kilometers east to west, the dunes rise and fall like knife-cut ridges, emitting thunderous roars when travelers slide down their slopes, creating the unique acoustic phenomenon known as "sand peaks singing under clear skies." Nestled between these towering dunes lies the Crescent Moon Spring, its limpid waters shaped like a new moon. Despite being surrounded by shifting sands for millennia, the spring never dries up, maintaining a constant depth of about 1.5 meters—a wonder made possible by a unique geological structure where fault-seepage replenishment and monsoon-driven circulation maintain perfect equilibrium.

Han Dynasty records already noted how "the sand's song could be heard within the city walls." By the Qing Dynasty, the Temple of the Medicine King complex built by the spring reflected in its jade-green waters, composing the breathtaking scene of "dawn-lit clarity at the moon spring." When sunset paints the dunes gold and crimson, and camel caravans trace silhouettes along the ridges while the spring mirrors starlight and distant snow peaks, this desert oasis transforms into the Silk Road's most dreamlike natural landscape, embodying nature's sublime creative power.

Yumen Pass: The Poetic Soul of the Frontier in a Desert Citadel

Standing sentinel 90 kilometers northwest of Dunhuang, this Han Dynasty fortress (established 121 BCE) guarded the vital northern route of the Silk Road. The surviving earthen walls of its square ramparts—Xiaofangpan City—rise 9.7 meters, forming a complete border defense system with nearby Han-era Great Wall sections and the Hecang military granary. The pass lives eternally in China's literary consciousness through Ban Chao's lament ("I dare not hope to reach Jiuquan Commandery, only to re-enter Yumen Pass alive") and Li Bai's verses ("Winds howl across ten thousand miles, sweeping through Yumen Pass"), its sunbaked clay embodying the frontier's poetic spirit.

Archaeological finds like the "Commandant of Yumen" bamboo slips attest to Han border control systems, while the rammed-earth construction with reed layers remains visibly intact. At sunset, when the ruins glow blood-red, these wind-scarred walls still whisper two millennia of homesick soldiers' longing—their sighs now harmonizing with distant train whistles along modern railways, composing a timeless ode to the frontier.

Today's Dunhuang bridges past and future: guardian of world heritage, pioneer of modern culture. The "Encountering Dunhuang" immersive theater resurrects history through technology, while the Dunhuang Academy's digital projects immortalize millennia of art in the cloud. As night falls over Shazhou Night Market, where apricot leather water and donkey-meat noodles perfume the air, the city extends its ancient hospitality to 21st-century travelers—proving its soul remains as vibrant as its murals.